I agree with your perspective about the historical perspective with the introduction of the white people assertions toward the beliefs of their spirituality and that expressed by the indigenous people of that time. The "new culture" to squashed that belief.Canadian Tom Harpur wrote that modern day religious scholars began to realize that indigenous people in this hemisphere possessed what are some of the most sophisticated and deeply held spiritual beliefs in the world.

Over all I see in a sense what you are saying that what could have befell the indigenous peoples is what could have fell upon the generations that exist now upon the planet by some alien society as an act of evolution and change with those same correlative situations as it did in our past. Many fictions written in this context today.

But again these are the finer mental states of existence of belief structures, polarization and centralization of such beliefs are "matter states" in the conquest of how we may perceive that evolution.

LEE SMOLIN- Physicist, Perimeter Institute; Author, The Trouble With Physics

Thinking In Time Versus Thinking Outside Of Time

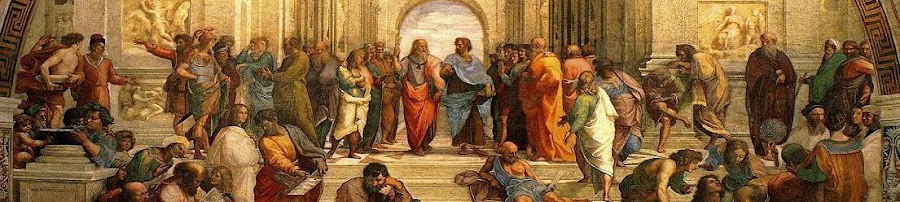

One very old and pervasive habit of thought is to imagine that the true answer to whatever question we are wondering about lies out there in some eternal domain of "timeless truths." The aim of re-search is then to "discover" the answer or solution in that already existing timeless domain. For example, physicists often speak as if the final theory of everything already exists in a vast timeless Platonic space of mathematical objects. This is thinking outside of time. See:A "scientific concept" may come from philosophy, logic, economics, jurisprudence, or other analytic enterprises, as long as it is a rigorous conceptual tool that may be summed up succinctly (or "in a phrase") but has broad application to understanding the world.

Lee Smolin does not obviously like the abstractions in the mathematical realm, and prefers to set the pace for scientific realism by denouncing the historical past with regard to foundational approaches by Plato Thales and others who were our forefathers of expression. Like Hawking, he is seeking to set foot in the realism of today?

So I am struggling with what we can define as "outside time" is no more then the belief of, while in science we are asking to deal with a methodology that is repeatable by expression, so how can we say spirituality is of a kind of substance or can exist amongst all substances and does not exist outside of time?

In dealing with the opinion of Hawking and Smolin I raise the question of Meno,

SOCRATES: But if he always possessed this knowledge he would always have known; or if he has acquired the knowledge he could not have acquired it in this life, unless he has been taught geometry; for he may be made to do the same with all geometry and every other branch of knowledge. Now, has any one ever taught him all this? You must know about him, if, as you say, he was born and bred in your house.SEE:Meno by Plato

MENO: And I am certain that no one ever did teach him.

SOCRATES: And yet he has the knowledge?

MENO: The fact, Socrates, is undeniable.

SOCRATES: But if he did not acquire the knowledge in this life, then he must have had and learned it at some other time?

MENO: Clearly he must.

You actually quoted from a post that dissappeared when providing the links for the cultural Books of the Dead. MacDougall reference and materialism. My point was to supply the Macdougall reference to show how spirituality from my perspective is much lighter and really can't be measured in the way you captured the quoted statement I have suggested.Spectrum wrote: Macdougall's mistake was to believe that spirituality could actually weigh something?I have no idea except to say that some scientists have said that certain phenomenon may not be detectable by our five senses as developed throughout our evolution. Astronomer Lord Rees suggests that we may need to evolve physically and otherwise a lot further in order to fully understand the universe. And I can see that. If we have evolved in a corner of the universe where atomic matter rules, then of course scientists are going to know a lot about physical matter, which is about 4% of everything that there is.

It goes back to the panel I provided about the weighing of the heart against the feather as truth. To me, it is about Gravity and how we are looking at it. Conceptually modelling according to the questions of a theoretical unification of all the forces. Where gravity actually begins and is inclusive. I really have to be careful here of my statements so as to maintain a mainstream correlative thinking that is current and correct. There is so much to remember.

That's interesting as it related to my own research on that topic. Developing the concept about our "metal imagery" according to some scale was implemented in the construction of the geometry of the pyramid. I tried scaling the substance of thought as a elementary consideration of where and what we grab onto in life so as to show that the harboring of thought in such a domain, reveals how close indeed we court the matter distinctions of the world we live in.Apparently some pyramidologists believe that if they substitute years for inches, the great pyramid becomes a prophetic calendar of human events culminating in a forked path to our future. A similar dual future is predicted by prophecies according to Hopis of the Americas. Time is a river that flows and branches into forks and even whirlpools according to Einstein.

Newton the Alchemist

Newton's Translation of the Emerald Tablet

Metal should read Mental, but using the analogy of what Gold men/woman are is as much a part of the allure of chymistry as a novel idea of bettering ourselves is an inclusive thought as well.

It is true without lying, certain and most true. That which is Below is like that which is Above and that which is Above is like that which is Below to do the miracles of the Only Thing. And as all things have been and arose from One by the mediation of One, so all things have their birth from this One Thing by adaptation. The Sun is its father; the Moon its mother; the Wind hath carried it in its belly; the Earth is its nurse. The father of all perfection in the whole world is here. Its force or power is entire if it be converted into Earth. Separate the Earth from the Fire, the subtle from the gross, sweetly with great industry. It ascends from the Earth to the Heavens and again it descends to the Earth and receives the force of things superior and inferior. By this means you shall have the glory of the whole world and thereby all obscurity shall fly from you. Its force is above all force, for it vanquishes every subtle thing and penetrates every solid thing. So was the world created. From this are and do come admirable adaptations, whereof the process is here in this. Hence am I called Hermes Trismegistus, having the three parts of the philosophy of the whole world. That which I have said of the operation of the Sun is accomplished and ended.

Many did not like this part of Isaac Newton's research but to me even with all the failures of Newtons "mental state" he was trying to better himself, and that is what the Books of the Dead represented to me about trying to understand matter creation in the sense of what we gather together to become who we are. That is a consistent feature of living beings that what gathers around our human feature, gathers around all things? Matter gathers around "a spiritual principal" from inside each of us.The Errors & Animadversions of Honest Isaac Newton

by Sheldon Lee Glashow

ABSTRACT:

Isaac Newton was my childhood hero. Along with Albert Einstein, he one of the greatest scientists ever, but Newton was no saint. He used his position to defame his competitors and rarely credited his colleagues.His arguments were sometimes false and contrived, his data were often fudged, and he exaggerated the accuracy of his calculations. Furthermore, his many religious works (mostly unpublished) were nonsensical or mystical, revealing him to be a creationist at heart. My talk offers a sampling of Newton’s many transgressions, social, scientific and religious.

The Sun then becomes a interesting feature of what "rays of creation" may mean as it gives life to all that falls under it's light that such a light could have existed inside of us as well. That we came from such a place as to exemplify that we are being first of the true signs of spirituality and then become all that falls under these rays of creation.

The standard model of particle physics is a self-contained picture of fundamental particles and their interactions. Physicists, on a journey from solid matter to quarks and gluons, via atoms and nuclear matter, may have reached the foundation level of fields and particles. But have we reached bedrock, or is there something deeper? Savas Dimopoulos

A refractory status of light itself and Thomas Young's question about spectrum of light and being.

Objects like the pyramid were shadow markers and were part of the history and development of concepts of geometers and angles of Euclid in my views. This is a materialistic explanation while the pyramid itself is a model for understanding the matter creation and sub developmental model of such scaling of human thought. This represented in my views as an attempt to help people of the times to understanding the truth and comparison of what values we hold to heart and our own evolution of being.

|

| Newton Prism Experiment |

The pyramidal model of refractions is a display of the light representation of the spectrum of possibilities, as a relational experimental model in my mind of something quite ancient in it's notion, is applicable in the views of the science today. Something that is forgotten, but as a attempt of all our remembrances whether we like to admit it or not, is a universal understanding of our depth of being and our loss of memory as we are immersed in materiality.

To me this is a aspect of understanding how ideas emerge as if from a world Smolin liked to assign toward "outside of time" and a diversion of the quest to understand aspects of materiality as "not in time." That is my disagreement of him and his thoughts as it relates toward. The "idea of symmetry" and how this is assigned as a relational aspect of the idea of "outside of time." We are of such perfection that such a beauty is simplified in our own existence as spiritual beings that we each contain this within ourselves? This possibility of becoming in the world of materiality.