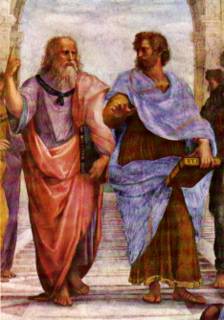

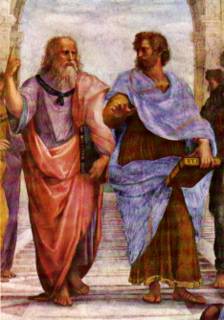

Raphael, School of Athens, fresco, 1509-1511 (Stanza della Segnatura, Papal Palace, Vatican) See: Raphael, School of Athens

See Also:

Utopia (pronounced /juːˈtoʊpiə/) is a name for an ideal community or society possessing a seemingly perfect socio-politico-legal system.[1] The word was invented by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island in the Atlantic Ocean. The term has been used to describe both intentional communities that attempted to create an ideal society, and fictional societies portrayed in literature. It has spawned other concepts, most prominently dystopia.

Woodcut by Ambrosius Holbein for a 1518 edition of Utopia. The lower left-hand corner shows the traveler Raphael Hythlodaeus, describing the island.

The word comes from the Greek: οὐ, "not", and τόπος, "place", indicating that More was utilizing the concept as allegory and did not consider such an ideal place to be realistically possible. The English homophone Eutopia, derived from the Greek εὖ, "good" or "well", and τόπος, "place", signifies a double meaning.It got my historical dithers up so as to pin down points of views that may have inspired cultures to look for new lands beyond the realms of thought each society was used too, and "hoped for" in some better form.

Utopia (book)

Utopia (in full: Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo rei publicae statu deque nova insula Utopia) is a work of fiction by Thomas More published in 1516. English translations of the title include A Truly Golden Little Book, No Less Beneficial Than Entertaining, of the Best State of a Republic, and of the New Island Utopia (literal) and A Fruitful and Pleasant Work of the Best State of a Public Weal, and of the New Isle Called Utopia (traditional).[1] (See "title" below.) The book, written in Latin, is a frame narrative primarily depicting a fictional island society and its religious, social and political customs.

Utopia

Illustration for the 1516 first edition of Utopia.Author Thomas More Translator Ralph Robinson

Gilbert BurnetCountry Seventeen Provinces, Leuven Language Latin Publication date 1516 Published in

English1551 Pages 134 ISBN 978-1-907727-28-3

Despite modern connotations of the word "utopia," it is widely accepted that the society More describes in this work was not actually his own "perfect society." Rather he wished to use the contrast between the imaginary land's unusual political ideas and the chaotic politics of his own day as a platform from which to discuss social issues in Europe.

Undoubtedly we have no questions to ask which are unanswerable. We must trust the perfection of the creation so far, as to believe that whatever curiosity the order of things has awakened in our minds, the order of things can satisfy. Every man's condition is a solution in hieroglyphic to those inquiries he would put. He acts it as life, before he apprehends it as truth. In like manner, nature is already, in its forms and tendencies, describing its own design. Let us interrogate the great apparition, that shines so peacefully around us. Let us inquire, to what end is nature NATURE---Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 1803-1882

PHENIX, the Pioneering High Energy Nuclear Interaction eXperiment, is an exploratory experiment for the investigation of high energy collisions of heavy ions and protons. PHENIX is designed specifically to measure direct probes of the collisions such as electrons, muons, and photons. The primary goal of PHENIX is to discover and study a new state of matter called the Quark-Gluon Plasma.

PHENIX, the Pioneering High Energy Nuclear Interaction eXperiment, is an exploratory experiment for the investigation of high energy collisions of heavy ions and protons. PHENIX is designed specifically to measure direct probes of the collisions such as electrons, muons, and photons. The primary goal of PHENIX is to discover and study a new state of matter called the Quark-Gluon Plasma.But we know relatively little about how the circuitry of the brain represents the consonants and vowels. The chasm between the neurosciences today and understanding representations like language is very wide. It's a delusion that we are going to get close to that any time soon. We've gotten almost nowhere in how the bee's brain represents the simplicity of the dance language. Although any good biologist, after several hours of observation, can predict accurately where the bee is going, we currently have no understanding of how the brain actually performs that computation.

In center, while Plato

- with the philosophy of the ideas and theoretical models, he indicates the sky, Aristotle - considered the father of Science, with the philosophy of the forms and the observation of the nature indicates the Earth. Many historians of the Art in the face correspondence of Plato with Leonardo, Heraclitus with Miguel Angel, and Euclides with Twine agree.

In a reflective occasion drawn to the center of the picture of Raphael, I am struck by the distinction of "age and youth" as I look at Plato and Aristotle. Of what has yet to descend into the minds of innovative and genuine science thinkers to know that the old man/woman works in concert with the science of youth, and this is something yet has still to unfold.

This drawing in red chalk is widely (though not universally) accepted as an original self-portrait. The main reason for hesitation in accepting it as a portrait of Leonardo is that the subject is apparently of a greater age than Leonardo ever achieved. But it is possible that he drew this picture of himself deliberately aged, specifically for Raphael's portrait of him in The School of Athens.See:Leonardo da Vinci

PLato saids,"Look to the perfection of the heavens for truth," while Aristotle saids "look around you at what is, if you would know the truth" To Remember: Eskesthai

PLato saids,"Look to the perfection of the heavens for truth," while Aristotle saids "look around you at what is, if you would know the truth" To Remember: Eskesthai Bradbury on FAHRENHEIT 451 See also at Home with Ray

Bradbury on FAHRENHEIT 451 See also at Home with Ray

“Television gives you the dates of Napoleon, but not who he was,” Bradbury says, summarizing TV’s content with a single word that he spits out as an epithet: “factoids.” He says this while sitting in a room dominated by a gigantic flat-panel television broadcasting the Fox News Channel, muted, factoids crawling across the bottom of the screen.

His book still stands as a classic. But one of L.A.’s best-known residents wants it understood that when he wrote it he was far more concerned with the dulling effects of TV on people than he was on the silencing effect of a heavy-handed government. While television has in fact superseded reading for some, at least we can be grateful that firemen still put out fires instead of start them.Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451 Misinterpreted L.A.’s august Pulitzer honoree says it was never about censorship

School of Athens by Raphael

School of Athens by Raphael

He wanted to give a speech, but no remarks are allowed. “Not even a paragraph,” he says with disdain. Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451 MisinterpretedWhy would he just settle with shaking a president's hand while he was being misinterpreted and was left without a voice?

It all start off as "a dream" or "an idea." Where do these come from? Dialogos of Eide

This is the home that my wife and I had built in 1998. It was built on ten acres of land with a wide sweeping view of the mountains in the background. Although not seen here, you may have seen some of my rainbow pictures that I had put up over the years to help with the scenery we had.

This is the home that my wife and I had built in 1998. It was built on ten acres of land with a wide sweeping view of the mountains in the background. Although not seen here, you may have seen some of my rainbow pictures that I had put up over the years to help with the scenery we had. Here is a picture of my daughter-in-law and son's house in the winter of this last year. He still has some work to do, but as per our agreement, I help him, he is helping me.

Here is a picture of my daughter-in-law and son's house in the winter of this last year. He still has some work to do, but as per our agreement, I help him, he is helping me.  We purchased a 2 acre parcel of land with which to build the new home up top. I went into the bush with the camera and with about 2 feet of snow. It was not to easy to get around, so as time progresses,and as I put in the roadway and cleared site, you will get a better idea of what it looks like.

We purchased a 2 acre parcel of land with which to build the new home up top. I went into the bush with the camera and with about 2 feet of snow. It was not to easy to get around, so as time progresses,and as I put in the roadway and cleared site, you will get a better idea of what it looks like.

Articles on Euclid

Articles on Euclid The Room of the Segnatura contains Raphael's most famous frescoes. Besides being the first work executed by the great artist in the Vatican they mark the beginning of the high Renaissance. The room takes its name from the highest court of the Holy See, the "Segnatura Gratiae et Iustitiae", which was presided over by the pontiff and used to meet in this room around the middle of the 16th century. Originally the room was used by Julius II (pontiff from 1503 to 1513) as a library and private office. The iconographic programme of the frescoes, which were painted between 1508 and 1511, is related to this function. See Raphael Rooms

The Room of the Segnatura contains Raphael's most famous frescoes. Besides being the first work executed by the great artist in the Vatican they mark the beginning of the high Renaissance. The room takes its name from the highest court of the Holy See, the "Segnatura Gratiae et Iustitiae", which was presided over by the pontiff and used to meet in this room around the middle of the 16th century. Originally the room was used by Julius II (pontiff from 1503 to 1513) as a library and private office. The iconographic programme of the frescoes, which were painted between 1508 and 1511, is related to this function. See Raphael RoomsAll those who have written histories bring to this point their account of the development of this science. Not long after these men came Euclid, who brought together the Elements, systematizing many of the theorems of Eudoxus, perfecting many of those of Theatetus, and putting in irrefutable demonstrable form propositions that had been rather loosely established by his predecessors. He lived in the time of Ptolemy the First, for Archimedes, who lived after the time of the first Ptolemy, mentions Euclid. It is also reported that Ptolemy once asked Euclid if there was not a shorter road to geometry that through the Elements, and Euclid replied that there was no royal road to geometry. He was therefore later than Plato's group but earlier than Eratosthenes and Archimedes, for these two men were contemporaries, as Eratosthenes somewhere says. Euclid belonged to the persuasion of Plato and was at home in this philosophy; and this is why he thought the goal of the Elements as a whole to be the construction of the so-called Platonic figures. (Proclus, ed. Friedlein, p. 68, tr. Morrow)

The father of all perfection in the whole world is here. Its force or power is entire if it be converted into Earth. Separate the Earth from the Fire, the subtle from the gross, sweetly with great industry. It ascends from the Earth to the Heavens and again it descends to the Earth and receives the force of things superior and inferior. By this means you shall have the glory of the whole world and thereby all obscurity shall fly from you. Its force is above all force, for it vanquishes every subtle thing and penetrates every solid thing. So was the world created. From this are and do come admirable adaptations, whereof the process is here in this. Hence am I called Hermes Trismegistus, having the three parts of the philosophy of the whole world. That which I have said of the operation of the Sun is accomplished and ended.Sir Isaac Newton-Translation of the Emerald TabletSee: Newton on Chymistry

If we watched of distant spot, of century XX aC emphasizes Hermes Trismegisto, - tri three, megisto megas, three times great; perhaps the perception of infinite older than we have and takes by Mercurio name - for Greek and the Toth - for the Egyptians. Considered Father of the Wisdom and Sciences in Greece, in the cult to Osiris it presided over the ceremonies as priest and he was Masterful in Egypt like legislator, philosopher and alchemist during the reign of Ninus in the 2270 aC.

Etimológicamente speaking, of Hermes, the gr. hermenéuiein, “hermetic” - closed, “hermenéutica” - tie art to the reading of old sacred texts talks about so much to the dark as to which it is included/understood in esoteric form. Part of saberes that it accumulated transmitted through the Hermetic Books that only to the chosen ones between the chosen ones could be revealed. As much Pitágoras and Plato as Aristotle and Euclides were initiated in the knowledge of the Hermetic School.

Myths and metaphors, like dreams, are powerful tools that draw the listener, dreamer, or reader to a character, symbol, or situation, as if in recognition of something deeply known. Myth's bypass the mind's efforts to divorce information. They make an impression, are remembered, and nudge us to find out what they mean, accounting for the avid interest that Ring audiences have in the meaning of the story.1

The Alchemists attempted to perfect the One Thing of Hermes, what they called the First Matter, by using specific physical, psychological, and spiritual techniques that they describe in chemical terms and demonstrated in laboratory experiements. However, while the alchemists spoke in terms of chemcials, furaces , flasks, and beakers, they were really talking about the changes taking place within their own bodies, minds, and souls.2

I took the picture at a time of day when the tide was at exactly the right place to create this image: when the surface of the water reflected the underside of the bridge and they combined, together they produced what I named the Golden Rectangle as a nod to Pythagoras (my hero). The sensation I experienced at the time was of balancing consciousness and feeling.

By 'dilating' and 'expanding' the scope of our attention we not only discover that 'form is emptiness' (the donut has a hole), but also that 'emptiness is form' (objects precipitate out of the larger 'space') - to use Buddhist terminology. The emptiness that we arrive at by narrowing our focus on the innermost is identical to the emptiness that we arrive at by expanding our focus to the outermost. The 'infinitely large' is identical to the 'infinitesimally small'.The Structure of Consciousness John Fudjack - September, 1999

In this metaphor, when we are seeing the donut as solid object in space, this is like ordinary everyday consciousness. When we see the donut and the hole at its center, this is like a stage of realization in which 'form' is recognized as 'empty'. When we zoom in extremely closely and inspect the 'emptiness' at the center, or zoom out an extreme distance away from the object and the donut seems to disappear and we have only empty space - this is like certain 'objectless' states of awareness that can occur in meditation. But the final goal is not to achieve the undifferentiated state itself; it is to come to the special perspective that allows us to continue to see all three aspects at once - the donut, the whole in the middle, and the space surrounding it - this is like the 'enlightened' state, in this analogy. 10 The innermost and outermost psychological 'space' (which is here a metaphor for 'concentrated attention' and 'diffused attention') are recognized as indeed the same, continuous.

Our attempt to justify our beliefs logically by giving reasons results in the "regress of reasons." Since any reason can be further challenged, the regress of reasons threatens to be an infinite regress. However, since this is impossible, there must be reasons for which there do not need to be further reasons: reasons which do not need to be proven. By definition, these are "first principles." The "Problem of First Principles" arises when we ask Why such reasons would not need to be proven. Aristotle's answer was that first principles do not need to be proven because they are self-evident, i.e. they are known to be true simply by understanding them.

But, Aristotle thinks that knowledge begins with experience. We get to first principles through induction. But there is no certainty to the generalizations of induction. The "Problem of Induction" is the question How we know when we have examined enough individual cases to make an inductive generalization. Usually we can't know. Thus, to get from the uncertainty of inductive generalizations to the certainty of self-evident first principles, there must be an intuitive "leap," through what Aristotle calls "Mind." This ties the system together. A deductive system from first principles (like Euclidean geometry) is then what Aristotle calls "knowledge" ("epistemê" in Greek or "scientia" in Latin).

This full length drama, set in Alexandria Egypt, 415 A.D. features the infamous Philosopher Hypatia, who has come into possession of a document that threatens the very basis of the new religion called Christianity; a document that some would do anything to destroy. Hypatia and a powerful Christian Bishop wage a fierce struggle for the soul of a young priest and for a document which tells a very different version of the life — and death — of Jesus. A true story.The writing was excellent as was the cast, and Bastian should be extremely proud of himself. (It is a mistake to call it “a true story”, though. It is a story based around historical events, which should absolutely not be confused with being a “true story”. Writers of synopses should not encouarge people to mix up the two.

Hypatia was the daughter of Theon, who was also her teacher and the last fellow of the Musaeum of Alexandria. Hypatia did not teach in the Musaeum, but received her pupils in her own home. Hypatia became head of the Platonist school at Alexandria in about 400. There she lectured on mathematics and philosophy, and counted many prominent Christians among her pupils. No images of her exist, but nineteenth century writers and artists envisioned her as an Athene-like beauty.

Letters written to Hypatia by her pupil Synesius give an idea of her intellectual milieu. She was of the Platonic school, although her adherence to the writings of Plotinus, the 3rd century follower of Plato and principal of the neo-Platonic school, is merely assumed.

Euclid belonged to the persuasion of Plato and was at home in this philosophy; and this is why he thought the goal of the Elements as a whole to be the construction of the so-called Platonic figures. (Proclus, ed. Friedlein, p. 68, tr. Morrow)

you can tell has a real thirst to get her mind around the issues, and who isn’t looking for a sound bite to take the place of a complicated story

Award-winning science journalist and author K.C. Cole will join the USC Annenberg faculty as a visiting professor of journalism in January 2006, the School announced Friday, October 28, 2005.

Plato - holding the Timaeus - Pointing up as a sign of his metaphysical belief in the higher world of the forms, shown with the face of Leonardo.

Aristotle - holding his Ethics with hand palm down, reflecting a more grounded approach to the problem of universals.

Heraclitus - melancholy and alone, shown with the face of Michelangelo